Your Online Friendship Centre

Exit Site

Your Online Friendship Centre

Arthur Bear Chief is a residential school survivor. The years since he attended Old Sun Residential School, from age 7 to 17, have not been easy for the man from Siksika First Nation in Alberta. While at the school he, like many other students who went through the residential school system, faced both physical and sexual abuse.

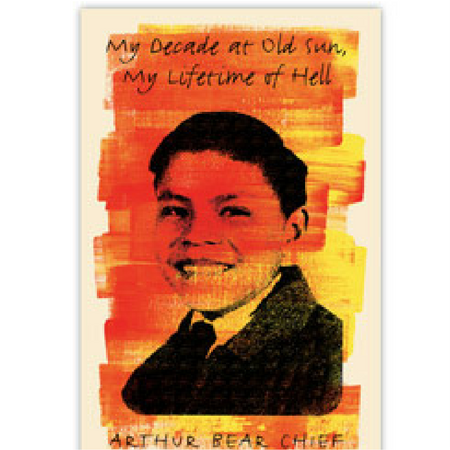

Bear Chief's new memoir, My Decade at Old Sun, My Lifetime of Hell, details the abuse he suffered at residential school and the toll it's taken on his life. It's not only an important account of what students were forced to experience, but also a chance for Bear Chief to share his story and take a step towards healing.

The following is an excerpt from Bear Chief's memoir, which will be published online for free by Athabasca University Press in December.

When I finally came forward in 1999 to file a complaint with the Merchant Law Group against the federal government for the abuse I suffered at Old Sun Residential School, I did so with a lot of apprehension. Not knowing what to expect, right from the beginning I said to myself, “This is not about money but for my own peace of mind, and for my late friend Nelson Wolf Leg.” Many years ago, on those terrible nights when we were both going through sexual abuse from our supervisor Bill Starr, we made a promise to each other to never say anything about what happened to anyone, not even our parents. We also made a pact that if one of us died, the other would come forward and talk about our abuse. I can still vividly remember Nelson, both of us lying in my bed crying and holding onto each other for protection, and scared out of our wits that Starr was going to come again. I was younger than Nelson, and I can remember him wiping the tears from my face and saying, “Keep quiet.”

As I recall these incidents, I am sitting here writing and crying for all those hurts I went through as a young boy. It seems like it was only yesterday when the assaults occurred, and no matter how hard I try, they never go away. I get emotional and cry for myself, even though all those years long ago I was taught by the older boys not to cry because it showed weakness. Now, some sixty years later, I am able to release my emotions without fear of showing weakness to others, although I prefer to cry when I am alone so no one can see me. That’s why I cry when I am all alone and my mind drifts back to Old Sun. My tears flow freely without fear of backlash or shame.

My abuses sat dormant inside of me all those years, and I never really thought too much about them. I guess in a sense I suppressed them in my head, and that’s why they never came out of me. When I filed my papers and had to tell my story, it was very painful to go back to those times so long ago that I had tried to forget. But nevertheless, I had to revisit my time at Old Sun Indian Residential School.

In 2002, my first lawyer, Tom Stepper, suggested in many of our conversations that I really should begin counselling for my residential school abuse. Reluctantly I agreed, and since I knew of no therapists, he suggested Donna Gould. I called her, and we began meeting after Health and Welfare said it would support five sessions at $75 per visit. This meant that I had to provide another $25 above their maximum, which was well worth the cost. Donna helped me a great deal to begin understanding what had happened to me and why I had problems. The letter she wrote for the lawyers involved in my case says a lot about what she learned about me in our sessions.

In October 2002, I was scheduled for my examination for discovery. My lawyers did nothing to prepare me for what I was about to go through. The only thing they said to me was, “Be yourself and tell the truth to best of your recollection and ability.” When the day finally came, I thought I could handle it. I thought I was a tough man. Boy, was I in for rude awakening! My first day lasted about six hours.

The federal government lawyer cross-examined me and challenged every statement I made. Throughout the day I broke down crying because of the pain of remembering my sexual abuse. I literally went back to that time and place. I had to explain every single detail of my sexual abuse. This I had to say to a woman I had never met before in my life. It never entered my mind what I would have to say. Because of my emotional state and being embarrassed, we broke up the sessions so I could get my composure. There were no support services where I could go for comfort and a few kind words to ease my pain. I was left to the dogs, and, just like in residential school, I had to suck up the pain and continue on.

I was embarrassed and degraded, for I had to tell a total stranger about my sexual abuse. It had been my personal secret all those years, and now I had to share it with a stranger. I was sickened by the whole process. When it finally ended six hours later, I went home feeling numb and very much violated by the proceedings. I opened a can of Coors Light, lay down in my bed, grabbed my other pillow to hold, and began to cry softly. My memory drifted back to those times at residential school when I ran out to the field so I could cry for my mother to help me. But, just like in residential school, she never came, and, as usual, I had to deal with it by myself. I must have drifted off to sleep and did not wake up until seven the next morning, my beer still lying beside my bed. I had not even touched it. I knew my next session was coming, and I would have to go through the same hell again.

I arrived at the lawyer’s office at nine for another round of cross examination from the government lawyer. Much to my surprise, she wanted to go back to some of my statements for clarifications and a few more questions. I told the lawyer that I was emotionally drained and not sure if I could go through another day like we did the day before. She said she understood and would go easy on me and not push me over the limit. It was short and easy for me. At lunchtime, she advised my lawyers that she was finished, but she reserved the right for another session if needed.

My lawyer talked to me before I left and advised me that I should have someone with me. He was a little concerned about my state of mind. I told him not to worry too much about me and that my best friend Coors Light was going to be my confidante and companion to ease my pain. Before I got home, I bought some beer for dealing with my problems. When I got home, I locked my door, shut my cell phone off, opened my beer, and sat down on the floor. My mind drifted back to Old Sun. It was like a flashback, so natural and normal that I started to cry as each event passed before my eyes like on a TV screen. You don’t want to think about them, but they come just the same. I cursed and swore at myself and the world and the system that sent me to that horrible place as a very young boy. I finally succumbed to the beer and drifted off into oblivion. If someone had handed me a gun at that time, I definitely would have blown my brains out. They would have saved themselves some money on my settlement.

The next day when I woke up, I was hungover, and all the pain of what I went through came back. The cycle had begun again. I did not have the opportunity to spend any time with someone who would listen to my grief. I said to myself, “But I am a survivor of residential school, so why should it be any different now? I’m so used to sucking it up and moving on.”

Learn more about My Decade at Old Sun, My Lifetime of Hell at aupress.ca.