Your Online Friendship Centre

Exit Site

Your Online Friendship Centre

It's no secret that mainstream media often represent Indigenous women as little more than victims of crime and injustice. Indigneous women know, though, that this perception is just a stereotype and that they are in fact powerful.

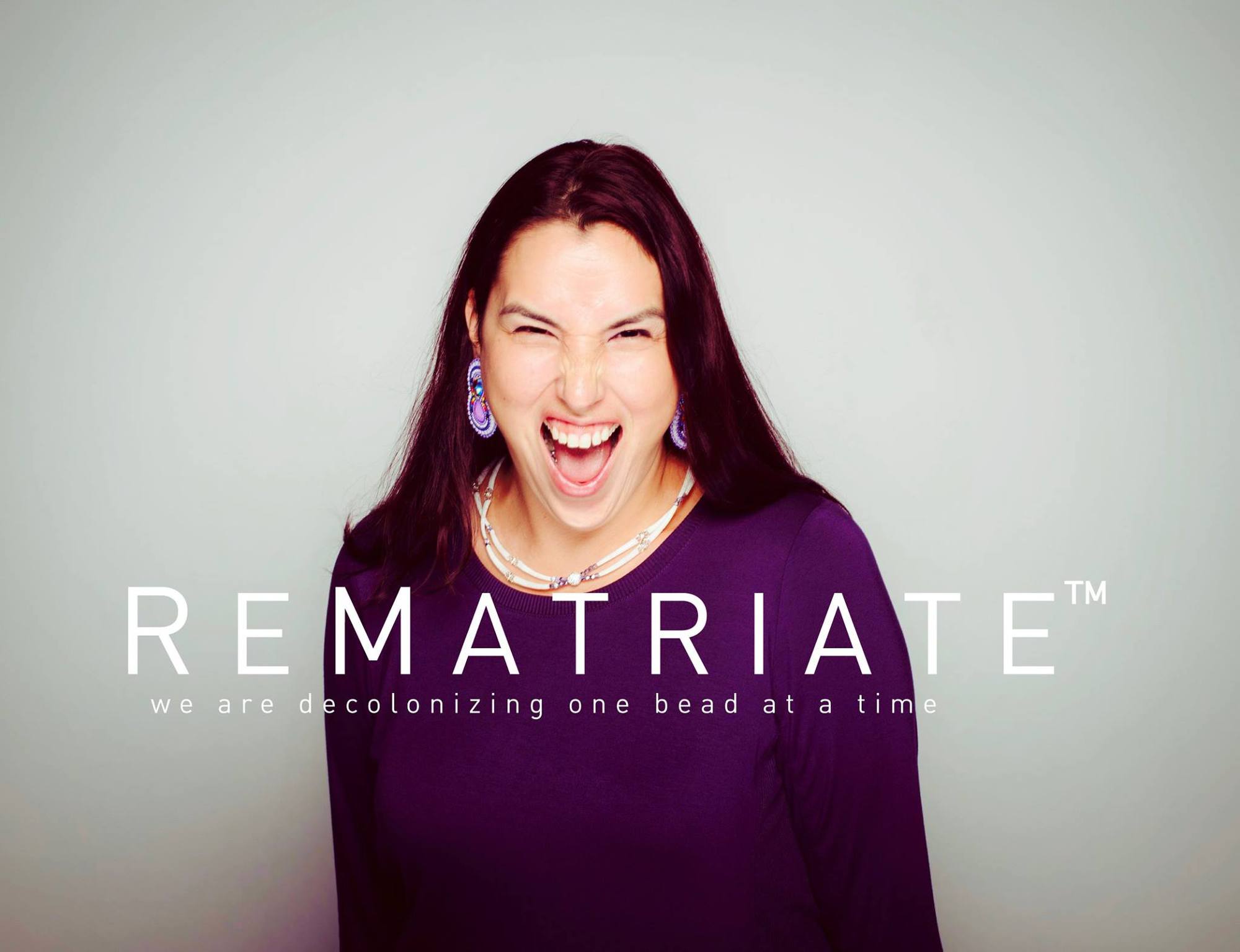

The ReMatriate Collective is working to reinforce this, and to fight the way Indigenous women are portrayed in the media. The collective is an online visual arts and decolonization movement intended to move the conversation around Indigenous women in the media into a more positive space by putting Indigenous women themselves in charge of how they are portrayed.

To do this, the collective goes straight to the source: Indigenous communities, where women are reclaiming their identities, self-expression and traditional ways of life with contemporary methods.

Nicole Cardinal, Dakelh (Carrier) from Stellaquo, British Columbia

The movement has a small core group of women across western and Northern Canada that run the collective as a volunteer-based passion project. Members Kelly Edzerza-Bapty Denver Lynxleg and Jeneen Frei-Njootli prepare the image submissions for ReMatriate.

The movement is simple: Indigenous women submit photographs of themselves that feel empowering to be posted on ReMatriate’s social media accounts (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and stay tuned for the collective's website). Each picture is accompanied by the woman's personal story and the territory she calls home.

Angela Hovak Johnston from the Kitikmeot Region, Nunavut and Inupiaq Marjorie Linne Tungwenuk Tahbone from Nome Alaska

The campaign initially started as a response to fashion designer DSquared’s disrespectful “DSquaw” collection and the question of how those involved could start to show Indigenous women in a more positive light and let people see the diversity and complexity of Indigenous reality.

ReMatriate has grown into a movement that aims to provide young Indigenous women with role models to look up to.

“It’s really important to see other Indigenous people represented in media to see what they look like, because native youth don’t really see themselves reflected in the larger dominant society," Lynxleg said. "It’s really important for youth to see themselves, their culture and values reflected in the media in a positive way.”

All the photos contain a ‘WE ARE’ statement “because we’re trying to relate to one another in a way that’s productive, so viewers can understand a context about us that’s positive," Lynxleg added. "We want people to recognize the differences between our cultures and how these things separate and distinguish us, but they are also things that make us proud and connect us.”

Edzerza-Bapty said that providing role models for young Indigenous girls to identify with has become an important aspect of this campaign, alongside showing the diversity and duality of contemporary indigeneity. Canada is an extremely diverse landscape and so are its Indigenous people, she added.

"Canada is an extremely diverse landscape and so are its Indigenous peoples," Edzerza-Bapty said. "It is important that people distinguish this and step out of the simple classifications of Pan-Indianisms, or in representing us as historic black and white photos. All of the photos in ReMatriate brightly portray that we are ‘Living Cultures.’”

Chloè Mustooch, Siktahtoh and Isga'a wiyami of the Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation, Alberta

Both Edzerza-Bapty and Lynxleg acknowledge that ReMatriate is intrinsically political. Indigenous women are challenging expectations by representing themselves in a way that empowers them, while also practicing their culture and traditions in a society that tried to eliminate them. It’s pretty badass.

Right now, Edzerza-Bapty, Lynxleg and the rest of the ReMatriate collective are working on widening their reach to more rural areas of Canada and to Elders who may not necessarily be connected online. Last year for Mothers’ Day, ReMatriate put out a call for women to submit photos of themselves with their life givers, which opened up the movement to more generations and inspired women to nominate members of their family for their accomplishments, too.

Edzerza-Bapty noted that a lot of women are shy about submitting photos, and it might be easier for them to nominate someone they admire. “We noticed women do a lot of quiet work that doesn’t necessarily have a lot of notoriety to it, and we want to honour that as well,” she said.

Lynxleg hopes ReMatriate has a lasting effect on women in Indigenous communities. “I hope ReMatriate’s promotion of lateral kindess could grow into a way of interacting with one another, that Indigenous women use as a model that could influence our behaviour to connect with each other in a good way.”

ReMatriate invites Indigenous self-identified women/womyn to submit photos of themselves, or nominate friends, relatives or community members (with their permission). Send all submissions to rematriate@gmail.com.

(Ta'une) Kelly Edzerza-Bapty is a daughter of the Etzenlee Matriarch and a member of the Tahltan Nation. She is an intern architect and designer whose practice focuses on revitalizing sovereign and self-reliant Indigenous land-based building practices and Indigenous-designed and built healthy communities.

Denver Lynxleg is a displaced yet proud member of Tootinaowaziibeeng First Nation. As a light skinned ikwe she has focused on projects that explore dialogues of resurgent cultural identity, emotional labour and decolonization.

Header photo of Sabrina Manitowabi, Odawa, Anishinaabe from Wiikwemikoong Unceded Territory.